By Kale Parker, a summer 2023 intern with CAIR Oklahoma. Kale is in his last year of law school at the University of Oklahoma College of Law.

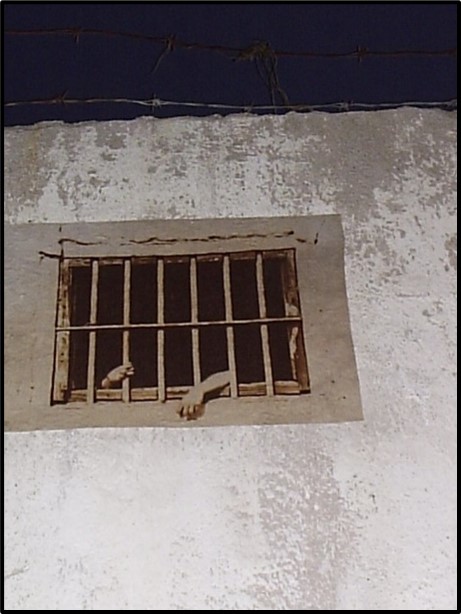

“Religious freedom in prison” is an oxymoronic phrase. The central idea of a prison is that it denies freedom to those who are imprisoned. If a person has no control over the places they can go to, the food they can eat, or the ways they can ultimately live their life, then denying them the freedom to worship how they please does not seem like a radical departure from the experience of prison. Nonetheless, the first clause of the Bill of Rights promises the American people that government shall not prohibit the free exercise of religion, and federal law extends that promise of free exercise to many incarcerated persons. While federal protection of free exercise is not unlimited in scope, it shows that some freedoms are too precious and fundamental to be denied, even for those incarcerated by the criminal justice system. Yet for many incarcerated Muslims, the liberty of free exercise, enshrined in the Constitution and federal law, exists as nothing more than ink on faded paper.

Faith cannot go beyond mere belief for these incarcerated Muslims, as the criminal justice system has repeatedly denied them the ability to practice Islam. Slate reported that a multitude of correctional institutions across the country have trampled on the free exercise of their Muslim inmates. For example, in 2018, a Nevada prison began denying space for incarcerated Muslims to hold Jumah (Friday) services. When one Muslim prisoner filed suit, what ensued “was a cat-and-mouse period during which the [prison] officials would alternate between saying that they had fixed the problem and continuing to deny prayer space and blaming things like a shortage of staff or prison lockdowns.”

If denial of communal worship was not egregious enough, some incarcerated Muslims cannot even eat in accordance with their religious beliefs. Discussed in an article by NPR, a report by Muslim Advocates stated that while “many state policies do provide full accommodation of Muslim diet requests, [o]thers, however, provide diminished diet substitutes or no substitutes at all.” Such lacking policies place Muslims in a tragic dilemma: they must either violate their sincerely held beliefs or starve. The justifications for dietary policies like these, as well as policies that burden Muslims generally, are unsurprising. The NPR article quoted Tariq Aquil, the originator of the halal meal policy for California’s state prisons, who said that “[s]ome decisions made by the prisons . . . come out of ignorance, concerns about costs, like [with] meal plans, or real security concerns like an emergency in the middle of Friday prayer.”

Incarcerated Muslim Deserve Better

While the administrative burdens described in both examples above are undoubtedly serious, incarcerated Muslims deserve more from prison officials who retreat behind the shortcomings of carceral bureaucracy. These shortcomings will always be convenient excuses for jails and prisons, but they do not represent the root of the problem. People can effectively tackle bureaucratic inefficiencies with a focused political and social will. But therein lies the issue: no such focus exists on behalf of incarcerated Muslims, as they are the victims of compounding indifference. As prisoners, they are viewed as unworthy of society’s care because they violated society’s laws. As Muslims, they are viewed as unworthy of society’s trust because their beliefs are not in lockstep with a Christian majority. To the members of a religious majority that have their freedom, incarcerated Muslims are not readily redeemable, and thus they are not worthy of the majority’s time, resources, or focus.

Imagine if prison officials prevented Christian prisoners from attending services on Sunday or from visiting with a chaplain. Imagine if they repeatedly told Christian prisoners that their Bibles were perpetually “lost” in the mail. Imagine if a Christian prisoner, who had fallen out of grace with both humanity and God, and who had believed that the only way to redemption was through faith and exercise of that faith, had no way to redeem themself. These hypotheticals are untenable for any group of people that champions religious liberty, yet they are realities for incarcerated Muslims across the country.

Taking Note of Similarities

While it may be easy to be indifferent to the struggles of someone who believes so differently, a Christian should consider the noteworthy similarities between Islam and Christianity. Not only are the lineages of both religions traceable to the patriarch Abraham, but they also share a common doctrinal thread: resolute belief. Being a Christian requires faith in the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ. Being a Muslim requires a recognition of tawhid, the divine oneness of Allah. Without uncompromising belief that these things are true, Christians and Muslims could not be Christian or Muslims. But even without the similarities, the Gospel of Luke should provide free Christians with the clearest guidance when considering the plight of incarcerated Muslims: “Do to others as you would have them do to you.” No Christian would want to be denied the ability to profess and exercise their faith, even when adjudicated as criminally guilty, so no Muslim should suffer the same.

In the end, many incarcerated Muslims seek redemption, both societal and divine. To achieve societal redemption, an incarcerated Muslim must serve their sentence. To achieve divine redemption, a Muslim must practice Islam, a term which literally means “surrender” to the will of Allah. As these incarcerated Muslims strive to achieve this second form of redemption, free Christians, that is, those who are not incarcerated, should not treat these Muslims with indifference. Incarcerated Muslims have already involuntarily surrendered most of their liberties; they deserve the opportunity to freely surrender through free exercise.