Islamic studies scholar John L. Esposito, a recent keynote speaker for an Oklahoma City event, discusses his career and interest in Islamic studies

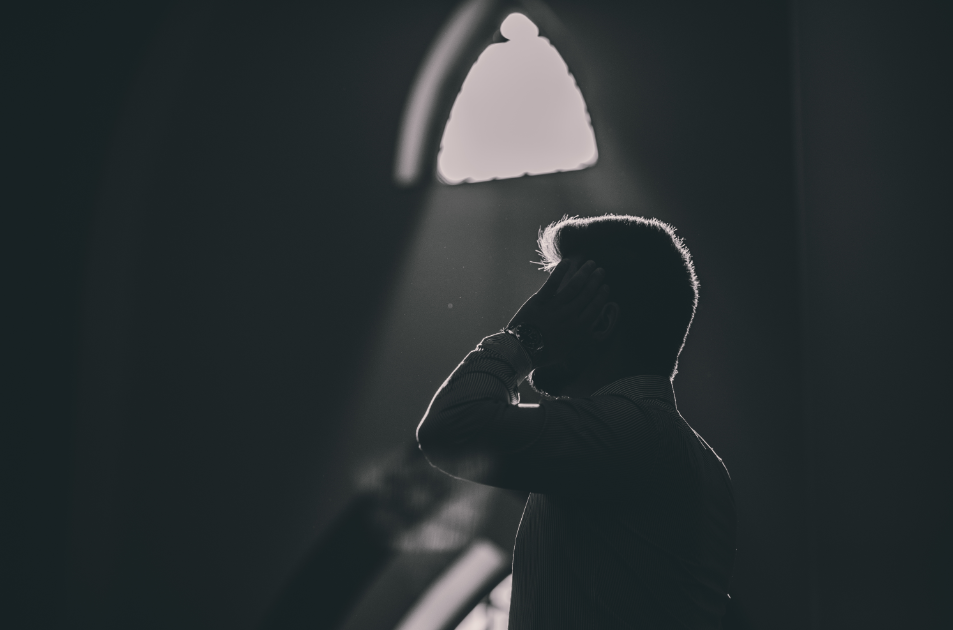

John L. Esposito set out to be a Catholic priest but instead became an internationally recognized Islamic studies scholar who has traveled the world.

Esposito, 73, gave the keynote speech at the annual dinner hosted by the Oklahoma chapter of the Council on American-Islamic Relations.

In a question-and-answer format (edited for clarity and space), Esposito discusses his background, how he became interested in Islam, plus his concern about the anti-Muslim tone — also called “Islamophobia” — in some U.S. communities.

Q: Talk about your religious background.

A: I was born and raised Roman Catholic, and at the age of 14, I went away to become a Capuchin Franciscan. I left at the age of 24 before becoming ordained as a priest. I wanted to be a priest, but something told me that it wasn’t something I wanted to do for the rest of my life. I wasn’t really quite sure what that meant. … I ended up teaching Catholic theology at a women’s Catholic school for six years. Eventually, I got a Ph.D., and my major was Islam and my minor was Hinduism and Buddhism.

Q: How did you become interested in Islam?

A: I was teaching at a Catholic college, and you need to get a Ph.D. The normal thing in those days, this would have been the late ’60s, early ’70s, would be that I would go to a Catholic university to do a Ph.D. in Catholic studies. The school that I was at had a doctoral program where you could major in one area of study and minor in two. A professor encouraged me to take Islamic studies and minor in Hinduism and Buddhism. I was older than most graduate students and married. I wanted to finish a degree quickly, so I was very, very reluctant but … I agreed to take one course in Islamic studies. I was just stunned … because in those days people always put Christianity and Judaism on one side and all the other religions on the other side — they were known as world religions or Eastern religions. So Hinduism and Buddhism were grouped with Islam, but when I studied Islam, I realized that no, they’re in the wrong family. They are part of the Jewish-Christian-Islamic family. That got me to discovering a whole history that I didn’t know and that we were never taught in school. Most Americans in my time even then didn’t realize that Islam is the second-largest religion and had no sense of the early centuries of Islam and the connections both structurally and historically.

Q: How did you become known for your knowledge of Islam and the Middle East?

A: I discovered when I finished (degree program) in 1974 that no one else was that interested. There were no jobs to teach Islam. But the unique thing was because I was trained in three religions as most of us were, I was ideal. It was right around that time that colleges and universities were developing religion departments and offering world religion courses. Then the Iranian revolution came and that was a sea change. I jokingly say I owe my career and my first Lexus to that. It put Islam, the Middle East, Muslim-West relations on the front burner and before it wasn’t even on the back burner — it was off the stove. From 1974 to 1979, I had four articles (about Islam) published. From 1980 to today, I have something like 45 books in 35 languages, and that would have never happened at that early pace.

Q: What made you interested in Islamic-Christian relations?

A: Obviously, I have a strong Christian background. I realized that if we are going to talk about a Judeo-Christian tradition, then we should be talking about a Judeo-Christian-Islamic tradition — that there is a connection. For example, just as Christians accept the biblical prophets and the revelation of the Old Testament but see a new covenant with Jesus, so, too, Muslims accept the revelation of the Torah to Moses and the Gospels to Jesus. If you read the Quran, you realize just how often Jesus is mentioned and realize that the Virgin Mary is mentioned more in the Quran than she is in the New Testament. Then you start to see the historical and intellectual connections, both in terms of coexistence and exchange and conflict.

Q: What do you think about anti-Muslim attitudes in some communities across the country?

A: “Islamophobia“ as I define it is not about people who have a kind of good fact-based criticism of the Islamic religion. There’s nothing negative about that. People are entitled to those types of criticisms. “Islamophobia“ is when you have an unfounded irrational fear that tends then to lead to bias, discrimination, hate speech and hate crimes. It’s an unfounded fear. What do I mean by that? … It means certainly one should be afraid of Muslim extremism. Most Muslims are afraid of Muslim extremism. The primary victims of Muslim extremists are people who live in the Muslim world in terms of numbers of people. That’s legitimate fear. It’s when you wind up brushstroking a religion and the vast majority of its followers and impose upon them a collective guilt for acts committed by extremists who may have grown up in a Muslim community but who, as I like to put it, “hijack their religion.” And we don’t do that with our other mainstream religions. We recognize that religion has its transcendence and its dark side. All religions have people who abuse and engage in violence.

Q: How do people combat “Islamophobia“?

A: First of all you don’t make the victims primarily responsible. For example, one of the great lines that people would give me, particularly for the first eight years after 9/11, people said Muslims don’t speak out against this (Muslim extremists). I have seen websites speaking out against this but you couldn’t get it into major media. More importantly, not every time there is an attack one should be expecting Muslims to jump out front of it, although they do it. Yes communities have to lift themselves up and fight for themselves, but it takes other communities to weigh in, other communities that represent the establishment or that were the groups that were discriminated against (at another time).