Fifteen years after the 9/11 attacks, Islamophobia is on the rise in America.

Anti-Muslim hate crimes are approximately five times more frequent than they were before 2001, according to the FBI.

The past year has been particularly brutal, especially in the aftermath of Islamic State-claimed attacks in Europe and the San Bernardino shootings last December carried out by a Muslim husband and wife.

More reports of mosque vandalism and attacks against those believed to be Muslim surfaced.

Anti-Muslim rhetoric has also been given an enormous boost of pseudo-credibility and prominence by Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump.

In December, Trump called to ban all Muslim travel to the U.S. (he has since called for “extreme vetting” of people from “territories” with a history of terror, though the ban is still a position on his campaign website).

The heightened rhetoric has exposed an alarming trend that has developed since 9/11 — Muslims are constantly and consistently cast as somehow un-American because of their faith.

The 9/11 attacks – carried out by 19 Islamic extremists – have no doubt changed how Muslim-Americans are perceived in this country, and those feelings have simmered for 15 years now.

Below, we explore the nine stories of Muslims-Americans affected by key flashpoints that have shaped the U.S. post Sept. 11, 2001.

They reflect on this year’s anniversary and current attitude toward them with stories of solemnity, hope, and, in some cases, despair.

The Survivor: ‘Muslims Died and Muslims Survived 9/11’

When the plane crashed into the north tower of the World Trade Center, Aziz Ahsan wrote off the sound as the sonic boom from one of the Concorde planes that had been flying around his office.

He didn’t realize the gravity of the situation until he was later caught in the debris field as the towers collapsed.

Ahsan narrowly made it out of the scene alive. And while he survived the worst terror attack on U.S. soil, as a proud Muslim America, it meant that Ahsan would also go on to live through the aftermath of fear and Islamophobia that would come, the side glances and hushed voices in public, the distortions in the media suggesting that those in his community were not true Americans at heart.

“Muslims died and Muslims survived 9/11,” Ahsan said. “People just automatically assume that Muslims were not the survivors.”

There’s an obscure symbolism in that Ahsan rushed on the morning of 9/11 to buy the new postage stamp commemorating Muslim holiday Eid. He went to three different post offices before finding what he was after. He bought every stamp in stock, his own small gesture to show that the Muslim American symbol was in demand and to ensure that everyone in his community would have stacks of their own.

He was still clutching the stacks of stamps when a photographer caught him on the train ride home; his eyes bloodshot, his clothes covered in dust.

Fifteen years later, Ahsan has pieces of the debris still trapped under his eyelids. Everyday he wakes up he has a piece of twin towers still with him, but it’s something he’d rather forget. For Ahsan, he wishes the date were like the 13th floor of old skyscrapers, where an elevator glides right over it, jumping from number 12 to 14.

“September 11 is like the 13th floor for me. I just don’t want it in my life,” Ahsan said.

The Grieving Mother: ‘We Are an Invisible People’

Talat Hamdani, a Pakistan-born American citizen, lost her son, Mohammad Salman Hamdani, 23, in the aftermath of the attacks at the World Trade Center. He had raced to the site to help the injured.

He wasn’t alone. Some 60 Muslims were killed in the 9/11 attacks. Their family members felt the same crushing uncertainty as other grieving families as they waited for days and months to find out if their loved ones were alive or dead — and the consequent heartache and despair after finding out it was the latter.

But these grieving Muslim families are often overlooked, Hamdani said.

“We aren’t counted. We are an invisible people. People are always saying ‘Muslim terrorists.’ But we died too. Our people died too.”

As she has every year since 2002, Hamdani will spend Sept. 11 with her other two sons, grieving for Salman in the country they call home, even if – due to what she describes as rising Islamophobia – it doesn’t often feel that way.

“It’s a hard day. We don’t do anything,” the 64-year-old retired school teacher said. “We just stay together and we shut down. We do not turn on the television, we cut off from the world and stay in our own little world. We might go for a drive, but we don’t address the day itself. What can you possibly say?”

Even today, Hamdani, who lives in Lake Grove, New York, is fighting for her son’s recognition as an NYPD cadet. Salman – who was initially wrongly suspected of being involved with the attacks – said ongoing discrimination against Muslims is a primary factor in why he isn’t being recognized. “The Muslim community is under siege,” she said.

The Lawyer: ‘Guantanamo Was Barbaric’

In January 2002, just five months after the largest terror attack on American soil, the U.S. opened a military prison in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. It was marketed to the American public as a place to detain the worst killers and terrorists in the world. In reality, it was a place uninhibited by the confines of international and U.S. law.

Rooted at the core of Guantanamo, at the very design and implementation, was a visceral Islamophobia, said J. Wells Dixon, a senior staff attorney at the Center for Constitutional Rights who represented detainees held inside the facility.

“There was a mass hysteria about Arab and Muslim men following 9/11,” Dixon said. “Guantanamo was designed to be prison for the Muslim men and boys who the United States government thought should not be entitled to protections of U.S. and international law.”

Then-Sen. Barack Obama built a core tenet of his 2008 presidential campaign on the promise to close Guantanamo. On his second day in office, President Obama signed an executive order to release the 245 detainees still held at the naval base and to shut down the facilities within a year.

Despite his promises, Obama approaches the final days of his second term with the Guantanamo Bay detention center still in operation. With political will waning in pledges to close Guantanamo down, the facility represents the hardships of reversing a policy built upon fear.

“What the United States did to Muslim and Arab men in Guantanamo was barbaric,” Dixon said. “How did it happen? When you’re so afraid of something or somebody that you don’t understand, there is a tendency to view that person as someone, something other than a fellow human being.”

The Mobilizer: ‘Go From Being a Liability To Be An Asset’

Weeks before voters hit the polls in the 2004 presidential election, Muslim-American leaders were made the punchline of a comedy sketch on “Saturday Night Live.” The laugh line, set up by Tina Fey, then-anchor of the recurring faux-newscast “Weekend Update,” was harmless and playful — it wasn’t so much a joke as an uncomfortable truth.

“Several major American Muslim groups gave their endorsement to John Kerry this week,” Fey said.

“In response, Kerry was like, ‘Aw, no, really, thanks, I’m good. Thanks, though. Thank you.'”

That sketch, and the entire climate around the 2004 election, was telling of the lagging social and political capital that the Muslim community had been able to build up since 9/11, said Khurrum Wahid, a prominent attorney.

“That was a joke because Muslim groups were really seen as a liability,” Wahid recalled of the “SNL” sketch. “How do we go from being a liability to be an asset?”

Wahid soon started Emerge USA, a nonprofit aimed at mobilizing Muslim-, Indian-, Pakistani- and Arab-Americans, registering them to vote and become politically active within the community.

Political engagement is an arena where Muslim-Americans lag behind the rest of the general public. Two-thirds of U.S. citizens who identify as Muslim (66 percent) said they are certain they are registered to vote, according to a 2011 survey conducted by the Pew Research Center. By comparison, that share is closer to 79 percent of the general public that is registered to vote.

Wahid said his organization’s sights are still in the future, but he’s already seeing the shift in his own college-age children today.

“I believe that Muslims are in a state of fighting for their survival,” Wahid said. “My daughter barely recognizes that. From her perspective, the big issues are class warfare and the differences between the haves and the have nots.”

The Ex-Politician: ‘The Easy Route Is To Blame Faith’

In 2009, Rashida Tlaib became the first Muslim-American woman to serve in the Michigan Legislature and only the second in history to be elected to any state legislature in the country. In 2014, she unsuccessfully ran for state Senate and candidly expressed the skepticism and downright racism she felt during that bid. “I ran for state Senate and people at the doors would tell me, ‘I don’t like your name.’ That’s code for ‘I don’t like your ethnicity.'” Once she received hate mail with the message, “A good Muslim is a dead one.”

Islamophobia, Tlaib says, has gotten worse. Immediately after the 9/11 attacks, “I remember being in law school and there was a tremendous amount of fear, but there were a lot of people saying, ‘This is not about Islam.’ There was a message of unification,” she said. “Now after the Iraq War and post-Afghanistan and ISIS and all that is happening at the same time with someone like Donald Trump running for office, suspicion based on faith is so heightened right now. I feel like it’s gotten 10 times as worse. … The easy route is to blame faith, and I think that’s what a lot of Americans are doing.”

Tlaib (who plans on running for public office again one day) has two sons, age 5 and 11. Raising children as Muslims in America has been particularly challenging. She recounted her oldest son recently coming home from summer school. “The kids were saying that Trump is trying to take over the world and that he wants to get rid of Muslims. Mama, where are we going to go?” he asked. Tlaib told him, “We don’t have to go anywhere. This is our country.”

The Imam: 15 Years Later ‘There Is More Fear and Suspicion’

Imam Muhammad Musri of Florida tried to dissuade Pastor Terry Jones when he sparked an outcry in 2010 over his plan to burn Qurans on the ninth anniversary of the 9/11 attacks. There was a climate of hate then – but it’s only gotten worse, said Musri.

Jones was a fringe figure in 2010, but his ideas have become mainstream. “This year, since the attacks on Paris and San Bernardino and Trump’s statements, it changed everything. It became visible hate,” said Musri. He added, “For American Muslims, 9/11 is a day we will never forget. It was a tragic event that was so historic that it changed our lives overnight, … While we are 100 percent committed to the U.S. as our country, the percentage of Americans who think otherwise has risen over the past 15 years. And today, the vast majority of Americans question our commitment, either openly or to themselves. They think that Muslims could not be loyal to this country, and Muslims have a different agenda, which is false.”

This year’s 9/11 anniversary coincidentally falls right before the Muslim holiday Eid al-Adha, which begins the evening of Sept. 12. During Sunday’s services, Musri said he would touch on the attacks and will note that many people who lost their lives on that day were Muslims too. In addition, he said, “We will be talking about remembrance of tragedy on 9/11 and how 15 years later things are not better but there is more fear and suspicion today than before and what should we do about it — reach out to our neighbors, invite the outside community through open mosques and open houses to engage the people and let them know who we are and there is no reason for this fear because we are all on the same team, against terrorism and trying to protect our homeland.”

The Advocate: Sharia Ban A ‘Solution In Search of a Problem’

A new anti-Islam movement was planting roots in the heart of the Great Plains.

It began with an Oklahoma ballot initiative in 2010. A resounding 70 percent of voters called to amend the state’s constitution to allow for a ban on the Islamic code of principles, known as Sharia law.

Muslims had lived in the region since the 1960s. But nearly a decade after the 9/11 terror attacks, fears crept up for Oklahoma voters that the Muslim culture posed an imminent threat to their way of life.

“It was a solution in search of a problem,” said Adam Soltani, executive director of the Council On American-Islamic Relations in Oklahoma.

It became the first in a wave of more than a dozen states to enact similar bans. Prominent political leaders within the tea party championed the issue from state to state, warning that Sharia threatened to undermine the rule of law and U.S. Constitution.

“They had already been so influenced by the emotion of fear,” Soltani said. “It reached to all corners of our state.”

Soltani’s group took the issue to court, arguing that the constitutional amendment was a dressed up version of religious discrimination. A federal judge ultimately agreed, and the language was changed to no longer target Islam.

But Soltani contends that the heart of the issue was based on a fundamental misunderstanding of what Sharia stands for, and what it means to have religious principles governing both private and public life.

“Sharia is not a common term we use. It’s not a term that we even talk about, it’s just ingrained within us and how we live, our relationship with God and our relationship with other people,” Soltani said. “It is based upon mercy and compassion.”

The Bereaved Brother: We ‘Come Together and Heal’

It’s been a little over a year and a half since the high-profile shooting deaths of three Muslim students in Chapel Hill, North Carolina – an attack that the victims’ family members believe was motivated by hate. Craig Hicks, a neighbor, has been charged with their murders and faces the death penalty at trial.

Farris Barakat, the brother of Deah Barakat – a victim of the North Carolina shooting – said Islamophobia has only gotten worse since 9/11, and in particular the past two years. “Nobody has been so outspoken about it as Donald Trump and has made a point to use it so politically,” he said, referring to Trump’s call to ban Muslim travel to the U.S.

The Barakat brothers were in an Islamic grade school during the 9/11 attacks. “We were sent home for the next two weeks,” Barakat recalled. “We received bomb threats at our school. It was the first time we were presented with this idea that Muslims or Islam could be behind it.”

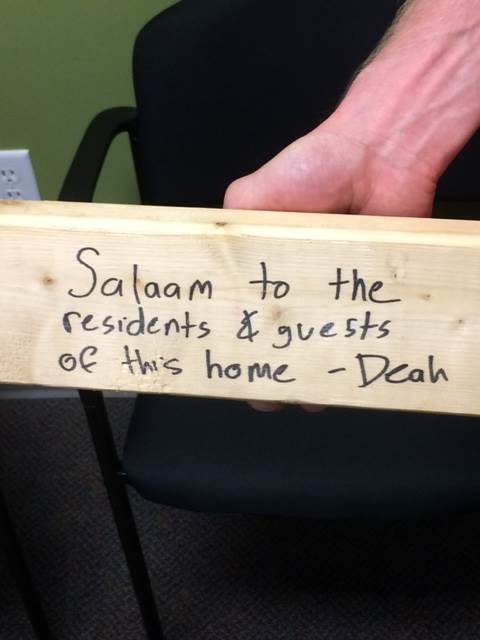

But Farris fondly remembers how religious communities have also come together in the aftermath of 9/11. On the tenth anniversary, he helped organize an interfaith build with Habitat for Humanity, working alongside his brother. At the end of the project, those who helped build a home for a family in need signed a plank of wood. Deah had written, “Salaam [peace] to the residents and guests of this home.”

Farris said his brother’s words “represented the actions of so many Muslims on that day — to come together and heal.”

The Fallen Soldier’s Family: Trump Doesn’t Know What Sacrifice Is

Khizr and Ghazala Khan, who lost their son, U.S. Army Capt. Humayun Khan, in service during the War in Iraq, offered a strong rebuke to Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump’s rhetoric in attacking Muslim-Americans.

Still, Trump dug in his heels by belittling the couple after their prime-time speech at the Democratic National Convention, sparking a major flash point in the presidential campaign that raised questions over Trump’s temperament in addressing the grieving parents of a fallen American soldier.