Muslims in Oklahoma, like other minority communities in the state, haven’t always felt secure in their homes and places of worship. Earlier this year, the Oklahoma chapter for the Council on American-Islamic Relations decided to spend a day at the Capitol meeting with representatives, holding workshops, and sharing their faith in a public prayer.

The 18-degree morning promising snow was met with protest. A man in a hoodie was projecting his voice above the heckling and the jeers:

Muslims want Islam to dominate this country! [Loud cheering and a “hear, hear!” from the crowd.] We don’t want a Muslim or the Lucifer in the White House. [Others concurring, “No! No!” and drowning him out.] Allah is Satan! Mohammad is in Hell! Allah is Satan! You’d all be killed by Jihadi John. Jihadi John would chop your heads off. Allah is Satan. Mohammad is in Hell.

James Gilles, from Indiana, holding a 5-foot-tall, slender black sign that read, “JESUS CHRIST, God manifested in the flesh, CRUCIFIED, RESURRECTED, And Coming Again Has a Pressure Cooker (The Lake of Fire) For Every Dead MUSLIM!” was also yelling, calmly, in a weighty monotone: “Mohammad was a pedophile. His favorite wives were only six and nine years old. You have blood on your hands!”

In contrast, smiling, snuggled close, Marty and Amy Monn, a mother-and-daughter duo, were there from the local Interfaith Alliance with supporters in equal or greater numbers to the anti-Islamic protesters. They formed two lines near the entrance to the Capitol building, allowing the Muslim conference attendees to walk between them as they sang “Amazing Grace” and other hymns.

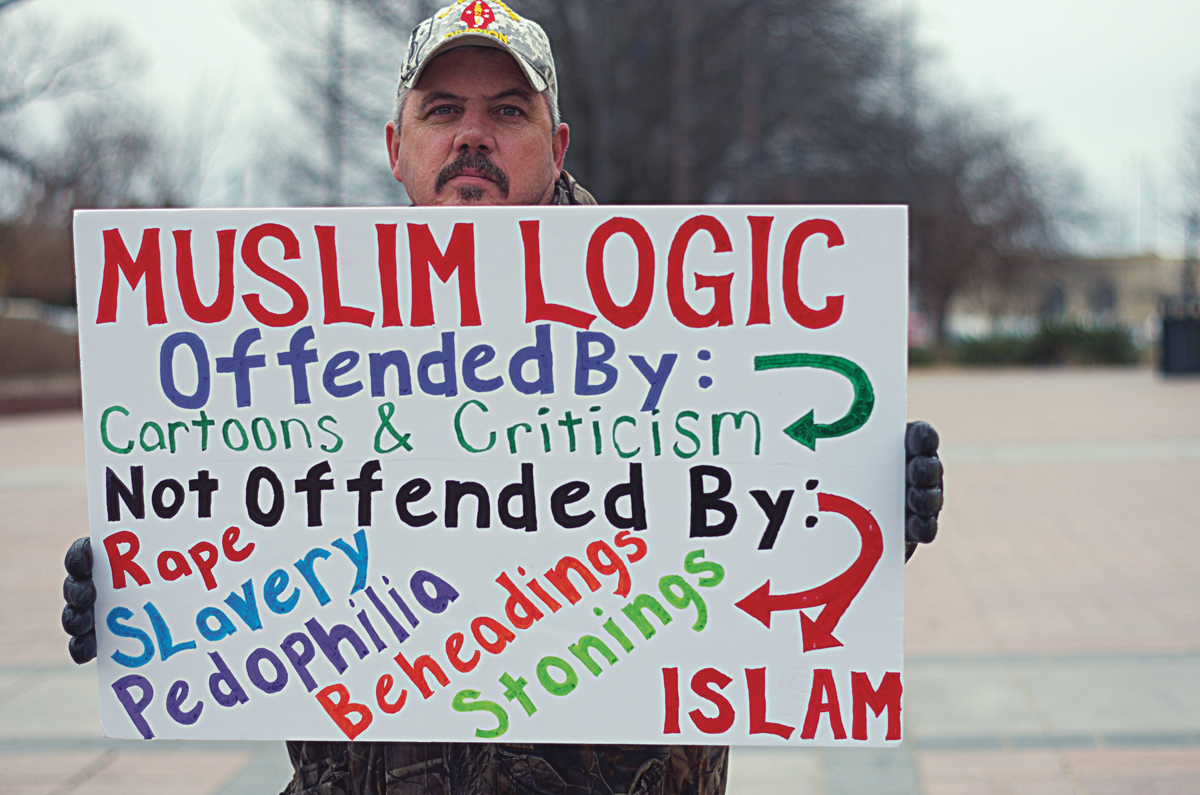

The protesters and the counter-protesters from an Oklahoma City interfaith group could be distinguished from each other by their dress: counter-protesters in long, wool coats, fur hats, ear muffs, knitted caps, and REI coats; protesters in camouflage, coveralls, American flags, combat boots. Clothing announcing privilege, security, comfort; clothing suggesting a battle ahead. Jeers, taunts, anger at the “Islamization of America” abound, but the protest was basically peaceful—if hurling “whore!” and “Mohammad was a pedophile!” at teenage Muslim girls walking up in hijab can be described as “peaceful.” For the first hours of the day, the protesters did not enter the building.

Stacy Pierce drove three hours from Locust Grove, Oklahoma, because of a song the Marine Corps sings about “the halls of Montezuma” and “the shores of Tripoli,” because of Glenn Beck, because of a struggle “over there” that’s coming home to roost. His soft brown eyes matched his gentle voice and he liked to end his sentences with an “alright?”—as much a reassurance as a call to arms. What happened in Dearborn, what happened in England, he said, can’t be allowed to happen here. He said:

I don’t have a problem with them learning what our government is about. What I fear is what Islam does: they try to take over the culture, they try to dominate the culture; it’s been proven historically over and over and over again, alright? They did this in England. Started out just like this. Observing government, alright?

Andrew Stodghill, originally from Tulsa, converted to Islam four years ago when he was 20. Most of his family still doesn’t know; his mother, though no longer worried he’ll become a terrorist, worries about his conservative uncles. Andrew converted in 2010, a month before Oklahomans voted by a 70-percent margin to ban Shariah law; his memory of his first visit to the local mosque is full of cameras and questions and protest signs. He’d been determined to keep the secret from his mother for the first six months:

I wanted to see if they would notice any change in my behavior. Before, I used to party quite a bit, you know, do the college thing: stay out till four or five in the morning, you know, debauchery. And so I wanted to cut that out of my life and I wanted to see if they’d notice a difference.

Instead, a month in, his mother made pork chops one night and broke down crying in the kitchen when he said he wasn’t hungry.

Walking up, he looked like George Washington, and though he refused to give his name, he said he was dressed as a “Minute Man” and was here to protest Islam in the United States. He told the reporter in front of me: “It’s like what the gays did. Act nice. Infiltrate. Muslims are the same.” As he was talking, I heard behind me from another protester, “Whore! Mohammad was a pedophile! We don’t want your Shariah law.” A woman in hijab, the object of the taunts, was trying to enter the Capitol. “Shame! Shame!” shouted other protesters.

One of them shoved me and pushed his poster in my face, blocking my camera. “Aren’t you here to be seen?” I asked. “No!”

Inside the Capitol are teens from Peace Academy, a private Muslim school in Tulsa. Bishar is 16 years old: eight years in Syria, eight in Oklahoma. Starla and Amera, juniors in high school, were both born in the U.S. Starla said, “I feel like the majority of people are very accepting and open-minded, so we don’t feel any big threat, there is the occasional shout-out or dirty look or something like that, but honestly I think many cultures experience that.” As the first female walked towards the Capitol earlier I’d heard, “Oh, there’s our first real live Muslim woman! Aloha snackbar! Go home!”

Just before the 2:00 pm, preparations for Jummah, or Friday prayer, were made in the main gallery on the second floor. In the gallery above, a group of protesters were having what appeared to be a heated discussion with Capitol security: voices raised, hands waving. As the rugs were laid out, Adam Soltani, local head of the Counsel on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR), and Imam Imad Enchassi, whose mosque sits on the western edge of the Oklahoma City, met in the background.

For a moment, as the prayer service began, all was quiet and still, and then the lilting call to prayer.

Less than a minute into the service a protester interrupted by loudly reciting the Lord’s Prayer.

Moments before he conducted the prayer service, Enchassi stood in front of a large painting commissioned to represent Oklahoma. It appeared to me that several shadows crossed his face as he stood there. Earlier that week, a representative in the state legislature had called the Muslim community in Oklahoma “a cancer” on society. Ostensibly, Enchassi was standing behind a podium addressing this great hall filled with Muslim men and women, praying separately, on their knees for Jummah. His words, however, could seem to address the Christians of Oklahoma: ties to Abraham, Hagar, Ishmael, David, Jesus, and Mary; his Native-American grandson from the Cheyenne tribe; his turkey at Thanksgiving stuffed with rice and garbanzos and spiced ground beef. “It sounds like a joke, but today the rabbi, the imam, and the preacher walked into these halls together,” he said.

We come with a message of love and a message of peace. We want you to look at your Muslims brothers and sisters, the citizens of the State of Oklahoma around you, and let me assure you that we’re not a cancer. We want to assure you that we are a vital part of this society, and when you look at a Muslim, always think of me as your brother from a different mother.

We are a nation of immigrants. Our strength is drawn from our diversity. What makes us stay great is that we cash in our diversity, and we’re a family. And we love one another. I’m not a cancer. Representative—I’m not a cancer!

If Muslim Day at the Capitol was a day of reaching out to the general public in Oklahoma, it may fall on deaf ears if local CBS News 9’s report is any indication: in their brief broadcast, they misrepresented the anti-Muslim protesters singing “Amazing Grace” rather than screaming “whore” at young teen girls. In fact, the hymn was sung by local Interfaith Alliance members, who were not interviewed, though their numbers at least matched the anti-Muslim protesters. News 9 also neglected to show the interruption of Jummah with the Lord’s Prayer, the most dramatic part of the day. The term most used in reference to the anti-Muslim protesters: “patriotism.”

Oklahoma’s Native-American and African-American communities have had their neighborhoods burned down and their land stolen. Even today, the only representation of African Americans in the historical paintings in the second-floor gallery is that of a half-naked slave working beside a steamboat; the most eye-catching representation of Native Americans in the building is a bronze sculpture of a man in stereotypical garb that those who were forced to live in Oklahoma after traversing the Trail of Tears didn’t even wear. The Muslim community in Oklahoma, aware of this history and the present climate, has a difficult task ahead if they are to overcome similar marginalization.

Originally published, with additional photography, in This Land: Summer 2015.